Indirect bonded restorations have become increasingly popular in the last couple decades. Such restorations require extensive knowledge about dental materials and bonding protocols. Tech- nological advances have changed the way a case is planned and executed. Most talented clinicians and dental technicians, however, agree that handcrafting remains the most refined way to fabricate beautiful esthetic restorations. The most important skill in this regard is knowledge and understanding of dental morphology.

Dentists and dental technicians must understand that “shape is the essence.” Falling in love with the beauty of natural dentition is the cor- nerstone of the Biomimetic Approach. This knowl- edge can only be acquired through observation, analysis, and practice of didactic methods.1 An ac- curate diagnosis is also essential in order to under- stand the underlying etiology. The mastery of these facets of dentistry will give a more satisfactory final outcome, leaving in second place the restorative material to be used. The success of esthetic and functional rehabilitations will be influenced by the knowledge and skills of the dentist and dental technician. Various clinical situations will call for different degrees of creativity and skills.ESSENTIALS OF DENTAL MORPHOLOGY

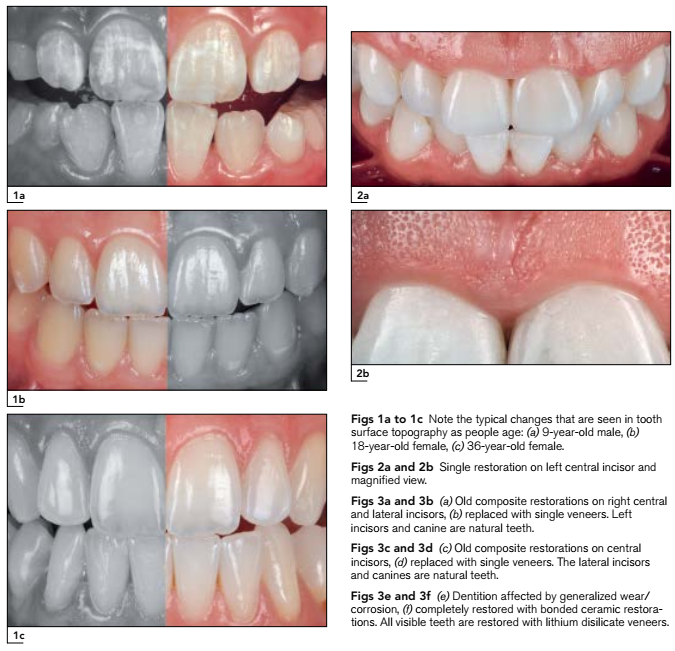

Beyond the choice for the restorative technique and mate- rial, there are objective elements that will provide a restora- tion with a superior level of esthetics and natural beauty. Certain basic esthetic parameters of human teeth have to be respected and are described in the literature. Form and dimension are undoubtedly among the key elements. Char- acterization implies specific effects of form, intense local colorations (spots, fissures, dentinal lobes, zones of dentinal infiltration), and phenomena of reflection or transmission of light (transparency, translucency, opalescence, fluores- cence). Such effects determine the age and character of a given tooth and have to be respected as well. Finally, the surface texture is closely related to color, a parameter that it influences directly. In fact, the surface topography, which can be very marked on certain young teeth, tends to dimin- ish when teeth get older (Figs 1a to 1c). The determining elements of texture are essentially oriented horizontally and vertically over the labial tooth surface. The horizontal component is a direct result of the lines of growth (lines of Retzius), leaving fine parallel stripes on the enamel sur- face, also called perikymata. The vertical component is de- fined by the superficial segmentation of the tooth in different developmental lobes. These morphologic characteristics vary over time.

Color is too often considered a major element with re- spect to the esthetic success of a restoration. However, a minor error concerning color might not be noticed if the other parameters have been well respected. It is important to emphasize that the most hand-skilled and knowledge- able dental technicians and dentists will be able to repro- duce these morphologic characteristics very faithfully, but they will never be perfect (Figs 2a and 2b).

Degrees of Esthetic Integration

All the criteria mentioned will have a different implication depending on the type of case to be restored. At least three degrees of esthetic integration can be described:

3. Restoration of an entire segment or full dentition. All esthetic parameters can be redefined and a maximum of freedom is given to the positioning and distribution of space for each tooth (Figs 3e and 3f).

Morphologic Alterations: Diagnostic Status of Tooth Structure Loss

A patient can present with existing teeth that have various degrees of alterations from the ideal esthetic objectives. A wide range of situations can be encountered. Patients can have genetic enamel changes that make teeth generally short, thin, flat, or conical—eg, microdontia, which may cause diastema, as in Fig 4a, or amelogenesis imperfecta. Me- chanical and chemical alterations of enamel will present a polished appearance, thinning of the incisal edges, yellow- ish color due to the visibility of dentin through the enamel, translucency of the incisal edges, chipping of the incisal edges, etc. In most severe cases (Fig 4b), dentin exposure occurs because the damage involves considerable reduc- tion of tooth volume. When an advanced stage is reached, the patient will easily recognize the yellowish discolora- tions of the teeth and the shortening of the dentition. Ultimately, the vertical dimension of occlusion can be altered.

At the other end of the spectrum, patients with minimal existing loss of enamel are more challenging to treat due to the dilemma of restorative material thickness. If possi- ble, an approach without enamel preparation will allow tooth structure to be maintained, which has several clinical advantages: lower risk of involvement of the pulp complex, absence of postoperative sensitivity, high bond strength to enamel, as well as reduced chair time, greater simplicity since it does not require provisionals or anesthesia, and predictability.4,5 The so-called “no-prep” cases should first be considered for direct freehand restorations (Figs 5a and 5b). Not every clinician, however, will feel comfortable restoring a whole segment of the anterior dentition with direct composite resins. In this case, the skills are trans- ferred to the dental technician and an indirect technique is used, which opens the debate about the various tooth preparation techniques.

Indirect Laboratory Process with Pressable Ceramics

Numerous techniques for indirect bonded esthetic resto- rations have been developed. In a historical pendulum, preparation techniques have evolved from a noninvasive approach (1980s) to a very aggressive style (1990s and 2000s) and are now returning to a simplified method with minimal or no tooth preparation involved.6 This is a logical result of increased awareness and demand by patients, who prefer to preserve the current state of their smile rath- er than being subjected to any treatment involving additional reduction of their teeth. Now more than ever, patients tend to select the least invasive therapeutic procedure, which allows the dentist to maintain all the remaining un- compromised tooth structure. In addition, the continuous improvement of the physicochemical properties of dental restorative materials as well as the refinement of manufac- turing processes has led to an increase of conservative treatment alternatives for esthetic and functional restora- tions. Margins of adhesive restorations are esthetically seamless. Even when physiologic gingival recession occurs, enamel margins remain invisible during aging (Fig 6).

Pressable lithium disilicate restorations have become increasingly popular. Like bonded all-ceramic restorations, they have the potential to reverse the esthetic manifesta- tions of aging and biocorrosion of the teeth and do not require a significant amount of tooth reduction due to the existing space provided by the missing tissues. Lithium disilicate restorations have been reported to be a very ver- satile material for either veneers, crowns, or implant resto- rations.8 Among the most significant advantages of the pressable ceramic technique are not only the simplified laboratory process (no need for special models) but also the thin margins and the possibility to make correction fir- ings even after finishing the restoration. The opacity and fluorescence might be different than obtained with feld- spathic restorations, but the difference in these qualities would be indistinguishable by a layperson; only highly trained clinicians and dental technicians might notice.

For both clinicians and technicians, significant removal of tooth structure may be both tempting and convenient when dealing with veneers or full-contour crown restora- tions. Tooth preparation can result in significant removal of intact tooth substance—up to 30% of the total tooth struc- ture in preparation for veneers with 0.5-mm-thick margins. In crowns with 0.8- to 1.0-mm-thick margins, twice as much tooth structure is eliminated compared to a conventional veneer preparation.9 Existing conditions can make teeth short, thin, and flat, which may provide insufficient reten- tion and resistance form, calling for even more invasive procedures such as root canal therapy and use of posts unless the adhesive approach is chosen instead.

It is important to make a careful analysis and diagnosis of the amount of enamel loss. This requires an additive ap- proach (wax-up and the corresponding mock-up), in order to preserve dental tissue and avoid unnecessary sacrifice of the tooth structure (Figs 7a to 7d).10 In other words, those cases with loss of tooth structure due to genetic conditions, biocorrosion, and wear should not require ad- ditional tooth preparation since the existing loss provides the clearance for the restoration. Because bonding to the enamel is quicker and simpler, the authors recommend making a significant effort to maintain as much enamel as possible. Small chamfers are ideal for thin ceramic margins but require significant skills and may result in exposed dentin when not achieved properly.11 Enamel thickness in the cervical area is about 0.3 mm,12 which is theoretically only allowing for featheredge preparations. In situations where the dentin is exposed, a very reliable alternative is im- mediate dentin sealing (IDS), which has proved to enhance the prognosis of indirect restorations such as composite/ ceramic inlays, onlays, and veneers. IDS appears to achieve improved bond strengths, fewer gap formations, decreased bacterial leakage, and reduced dentin sensitivity.

Impression taking is one of the restorative dentist’s greatest challenges due to the difficulty in controlling oral fluids such as blood and saliva. A precise impression re- mains of utmost importance in order for the dental techni- cian to manufacture a well-adapted restoration (Figs 8a and 8b). In cases for which featheredge preparations are chosen, no gingival retraction cord is needed, limiting the risk of damage to the periodontal tissues, bleeding, and gingival recession.15 This simplified approach is preferable, as it will save time, be less traumatic, and generate equi- gingival or supragingival margins, which are reported to be more gentle to the periodontium.16 However, there are situ- ations in which retraction cords might be required, such as large interdental diastemata, severe discoloration of the cervical area, and when slight displacement of the gingival contour is necessary to obtain a distally shifted zenith. A slightly intrasulcular margin will facilitate the realization of interdental mini-wings17 and/or masking of the cervical area. The laboratory process starts with the fabrication of master casts and their mounting on an articulator. Two sets of casts are fabricated from the same final impression. The first set is used to fabricate single dies for the fabrication of the monolithic base in wax and its adjustment once pressed (Figs 9a to 9k). The second set is used as a solid cast for creating the profiles and contours of the restora- tions while layering the porcelain on the monolithic base. The solid cast is also the best reference for the fine-tuning of interdental contacts. During this final treatment phase, most of the work goes to the reproduction of the tested and approved mock-up. In the authors’ opinion, photographs of a trial of the glazed restorations represent the most valuable tool in guiding the ceramist for any corrections.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Three cases with various degrees of esthetic integration are detailed to illustrate selected steps of the treatment.

Case 1—Restoration of One or More Anterior Teeth in the Presence of Intact Homologous Contralateral Teeth

The creative effort is clearly reduced by the presence of an intact homologous tooth serving as an “esthetic reference.” This does not mean that the ceramic work is easier to achieve, but the final result can be analyzed and directly compared with the control tooth.

A 22-year-old female patient presented with trauma in the anterior segment of the maxilla resulting from a bicycle accident. The right central and lateral incisors had suffered severe fractures, and the fragments could not be retrieved after the accident. The fractures had occurred a month be- fore, and the teeth had already been restored with a sin- gle-opacity monolithic composite resin, which showed a deficiency of surface gloss. The fracture pattern presented an oblique fracture line in a buccolingual direction with the margin extending apically, showing near–pulp exposure with thin residual dentin. Root canal treatment was consid- ered unnecessary since both teeth responded normally to the vitality test.

The patient was extremely conscious of esthetics and specifically requested that her teeth be restored “to look as similar as the neighboring teeth.” In discussing her expec- tations in more detail, it was understood that she wanted the most conservative treatment. Adhesive restorative tech- niques were selected in accordance with the guidelines proposed above (Figs 10a and 10b).

Vita classical shade guide was used for the shade se- lection. In this case, the shade selection appeared particu- larly challenging given the translucent details observed on neighboring teeth. Only a fine-grained diamond bur was used to remove the defective restoration; however, it was not totally removed, as it was determined that the adhesion procedure had been carried out properly. To finish the tooth preparation, all sharp edges were removed with a rubber wheel impregnated with aluminum oxide (Figs 10c and 10d). To make the final impression, retraction cord #0 (Ultra- dent) was only placed on the palatal aspect of the lateral incisor since the fracture reached a subgingival level (Fig 10e).

Using a solid cast, monolithic bases were fabricated and pressed in lithium disilicate, then stratified with a vol- ume greater than the actual size to control the contraction of the ceramic (Figs 10f to 10h).

Following try-in and acceptance by the patient, inner surfaces of the restorations were etched for 20 seconds using 5% hydrofluoric acid gel followed by ultrasonic cleaning (in distilled water for 2 minutes). After abundant rinsing and drying, silane was applied on the same surface (20-second application time and air dry, two times). Heat drying the silane (1 minute at 100˚C) is recommended.

The enamel surface was air abraded with 50-µm alumi- num oxide followed by etching. Filled light-cure bonding agent (OptiBond FL, Kerr) was applied on the prepared tooth surface and inner restoration surface and then load- ed with dual-cure luting material (Variolink DC, Ivoclar Viva- dent). The restorations were seated with finger pressure and light-polymerized. The excess luting material was re- moved, and the margins were covered with a glycerin gel and polymerized again. The margins were then finished with a scalpel and a scaler for the removal of excess resin and flashes (Figs 10i to 10p).

Case 2—Restoration of Two Homologous Anterior Teeth

This situation provides more possibilities concerning tooth form and position. Frequently, two central incisors must be redesigned. This endeavor is still limited, as the neighbor- ing and antagonistic teeth partially define the “artistic space.”

A 40-year-old female requested esthetic treatment be- cause she was uncomfortable with her defective compos- ite resin restorations in the maxillary central incisors (Figs 11a and 11b). Tooth preparation mainly consisted of re- moval of the defective restorations. Shade selection was particularly challenging because only the right central inci- sor was discolored. Bonded ceramic restorations can be easily influenced by the abutment tooth color; however, this does not necessarily mean that bonded ceramics are contraindicated and should not be an excuse for making a conventional crown with a metal or zirconia core for masking the dark color. In this type of case, the best choice will be the one that balances tooth-tissue conservation with the best mid- and long-term prognosis.

Hence, a more opaque ingot was selected (LT A1) to manufacture the base and then stratified to add some ef- fects and match as much as possible the characteristics of the adjacent teeth. Before the final bonding procedure, try- in paste confirmed that the ceramic base had insufficient masking ability on the discolored tooth. While a neutral lut- ing material could be used on the other tooth, the dark- ened tooth was luted with a modified resin (a third of white opaque added to the neutral shade). Having to use the lut- ing agent as a shade modifier is less predictable and is one of the limitations of working with monolithic ceramic bases with standardized levels of opacity compared to fully lay- ered restorations.

After the bonding procedure, a meticulous finishing procedure was carried out with a no. 12 scalpel and rubber tips (Figs 11c to 11j).

Case 3—Restoration of an Entire Anterior Segment

This represents a situation that requires redefinition not only with respect to the form and position of teeth but also the distribution of space for each tooth.

A 60-year-old man presented to a private practice. His chief complaint was that his anterior teeth kept chipping and getting shorter over time. The patient was in good general health, and his medical history was noncontribu- tory. During a previous dental evaluation, bruxism was di- agnosed as the main cause of loss of structure; however, he expressed that nobody ever suggested a treatment for this parafunctional habit. Clinical examination revealed that the patient also presented generalized dental biocorrosion in the form of concavities in the incisal and occlusal sur- faces due to the intake of vinegar in salads and citrus fruit juices (Figs 12a to 12c).

In addition to the loss of structure related to bruxism and biocorrosion, the patient presented extensive defective res- torations with poor marginal adaptation, residual roots, and edentulous areas that needed to be restored with dental implants.

The patient commented that he had abandoned the idea of undergoing any treatment because the options offered to him (endodontic treatments, post and crowns) were similar to those responsible for the tooth losses. After a relative suggested that he look for minimally invasive treatment options, his main request was to restore the ap- pearance of his teeth with the least invasive procedures possible.

Based on the compromised esthetics and function, a full-mouth rehabilitation was recommended to restore appropriate tooth proportions, modify the position of the incisal edge and occlusal plane, and increase the vertical dimension of occlusion (VDO) (Figs 12d and 12e).

An additive wax-up and corresponding mock-up were made on the anterior maxillary teeth to lengthen and redis- tribute the proportions. Following the patient’s approval, the mock-up was removed (Figs 12f to 12i).

IDS was performed in all areas where dentin was ex- posed. After preparation of the teeth, impressions of both arches were taken and models were mounted arbitrarily in centric relation records using a Lucia Jig at the increased VDO. Due to the minimally invasive approach, no provision- al restorations were required during the treatment, but soft resin provisionals (Fermit, Ivoclar Vivadent) were used in posterior teeth presenting defective restorations (Figs 12j and 12k).

Individual dies were used to wax up the restoration bases (anterior teeth) and the full anatomical restorations (posterior teeth). All wax-ups were then invested, burned out, and pressed with lithium disilicate ingots. Anterior bases were pressed using low-translucancy (LT) A2 shade, while the posterior teeth were pressed using high- translucancy (HT) A2 shade. Following adjustments and fitting on a solid cast (second pour of the original impres- sion), further cutback of the incisal edge and facial surface was performed and then layered with feldspathic porce- lain. The restorations presented appropriate blending (anterior and posterior) and were similar in shape to the wax-up/mock-up (Figs 12l to 12n).

Following minor adjustments for proper insertion and surface conditioning (etching, silane, adhesive resin wet- ting), restorations were delivered onto the air-abraded/ etched preparation surfaces with Variolink II (Ivoclar Viva- dent).

The occlusion was fine-tuned in centric occlusion since the occlusal scheme was modified. Each tooth was con- firmed to have at least one contact.18 Knowing that brux- ism negatively affects the success rate of any type of restoration (not only of veneers), even more so when teeth are nonvital,19 an anterior bite plane20 was provided to pro- tect the restoration from occlusal overload.21 No additional endodontic procedures were performed (Figs 12o to 12v).

CONCLUSION

Based on solid knowledge of dental morphology combined with an adequate diagnosis, it is possible to optimize the esthetic outcome of restorations with minimally invasive treatment. The success of esthetic and functional rehabili- tations will require various degrees of creativity and skill by the dentist and dental technician. Clinical situations have been presented to illustrate the range of possibilities that are available with adhesive dentistry—from simple com- posite resin additions, to more challenging unilateral indi- rect cases, to full-mouth rehabilitation.

Access